Hard and fast on Corona – Morocco style

For the last 8 months I have been teaching at a small liberal arts college in Morocco, Al Akhawayn University. It is located 1600m high in a small town in the Atlas Mountains, about 60 km from Fez.

Morocco went into full lockdown on Friday March 20 at 6pm, just after the 80th case was reported. Its reported trajectory has been very similar to that as New Zealand but, after a slow start, the response has been dramatically faster. At the moment there is a ban on all movement in public spaces, schools and universities are closed and education is on-line, non-essential work places are closed, and people have been issued certificates restricting their movement to two shopping trips per week. Borders have been closed for more than a week – this is for all people, residents and non-residents, in and out. The ban is indefinite, presumably until the government is convinced the threat is controlled.

I am writing this as the response is clearly different to that in New Zealand, even though both countries are reporting a similar infection experience. You may be interested to know what a preventive lockdown looks like.

First some background. Morocco has approximately 35 million people living in a country about the size of New Zealand. It is fairly poor, with average incomes about a quarter of those in New Zealand, and it still has a large rural population dependent on agricultural production. About four million people live and work abroad, primarily in Spain, France, and Italy. There are three national languages – Arabic, Berber, and French, but literacy levels are very low, perhaps only 70 percent. It is a very open economy with a large tourist sector and a fairly large French expatriate community. Casablanca is the largest city, with about three million people, and there are four other cities with a population similar to Auckland. The population density in these cities is very high – Morocco is famous for its medinas, medieval city centres which can house 100,000 people in a tiny maze of alleyways. If you have seen Tintin (or Jason Bourne) being chased by policemen in unnamed North African cities – well that gives you a pretty good idea of these medinas still look like.

Morocco is a constitutional monarchy with a history of very centralised power and the current King (Mohammed VI) is traditional (head of the Islamic faith) modernising (particularly with respect to female rights) and educated (Ph.D. from France). A parliament is elected to advise the King, but King is very involved with decision making. Morocco has large security forces, in part due to a legacy of a low-level civil war in Western Sahara (officially part of Morocco). Police and security forces are everywhere even in usual times.

Morocco’s first reported case of coronavirus was March 2, and by March 13 there were 12 reported cases. All of these cases were either foreigners or Moroccans returning from Europe. The 13th case, also reported March 13 was a cabinet minister, returning from a meeting in Europe. At the same time, the horror of what was occurring in Italy, Spain, and to a lesser extent France became very apparent. New Zealand had a similar number of reported cases at this stage but as we all know the true underlying situation may be very different as there can be a huge difference in reported cases and actual cases at the starting stages of a pandemic. The reported numbers in Morocco have appeared very low since the start, particularly given our really close proximity to Spain and Italy. (Spain is not only a 20 km ferry ride from Tangier, but there are two Spanish enclave cities in North Africa, with land borders with Morocco.)

Even though there were only 12 reported cases, on Friday March 13 the borders with Spain, France and Algeria were closed – flights to Italy had already stopped, and the ferry services to Italy were also closed. Closed means closed – there is no traffic either direction. By March 15 the borders were closed to all countries with all commercial flights curtailed. The inconvenience to foreigners and the large numbers of Moroccans overseas was ignored.

On March 13 an edict was also passed closing all schools and universities immediately. Universities have moved to online schooling. Our university started giving online lectures last week – I won’t say mine were any good, but after a few teething troubles we were up and running by Wednesday. Students are not allowed on campus, unless they have no where else to go.

On March 15/16 restaurants, cafes, gymnasiums and mosques were closed. The number of reported cases was still less than 40, but clearly increasing rapidly. Midweek, a list of essential industries was released, and only people working in these industries were allowed to go work. Schools, banks, food producers (including farmers) and retailers are on the list. You have to have a travel certificate issued by the government to go to work; these are inspected.

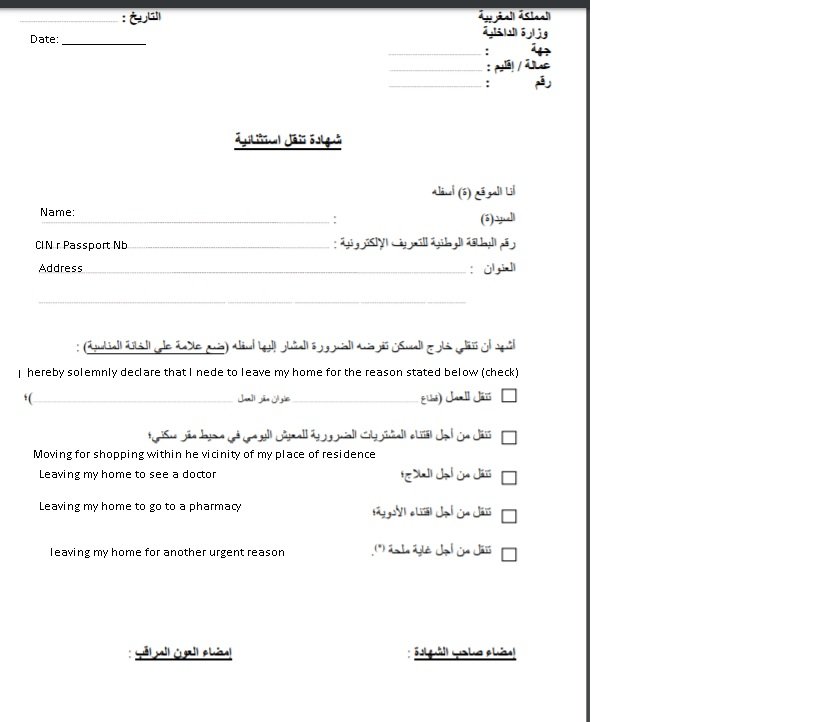

On Thursday March 19 it was announced there would be a total lockdown, starting Friday March 20 6pm and in place indefinitely. Intercity buses have been cancelled. People have been issued dated certificates by the government that allow them to go shopping in a local area twice a week, or to visit a medical facility. You fill in the form yourself, which is subject to inspection by police or security forces when you travel outside your home. An example is below.

People have also been given a list of hygiene procedures to follow when they return from a public space. The government is clearly extremely serious about preventing person-to-person transmission.

I returned from a last bicycle ride around the local countryside just before 6pm on Friday and the local town was deserted. I presume that there are very few people out on the streets anywhere. (I am incredibly privileged as I have been locked down into a 100 hectare university campus – a private space with very few remaining students – so I am as I can go outside, although not outside the fenced campus boundaries.)

The government has announced various economic and medical interventions. I don’t know how testing is conducted. The army has been converting its medical facilities for public use. Public transport within cities (tramlines, buses) is disinfected before reuse at the end of each line There is an economic package aimed at ensuring workers in affected industries (particularly hospitality and tourism) obtain some income, and the government has started a charity fund to help those in need (I don’t know how this distributes funds.) A large number of businesses and salaried people, particularly those in state owned businesses, are donating a month’s salary to the charity.

We are all hopeful that these measures will significantly slow the disease and prevent the terrible situation that is occurring in our neighbouring countries. Most European countries are reporting similar measures, but there is much less reliance on self-enforcement here. The speed of the response is, frankly, astonishing, but not out of line with the magnitude of the threat. After all, when the downside implications of an uncontrolled outbreak are compared to the downside cost of these preventative measures, the consequences of being too slow rather than too fast seem rather worse.

Well, that’s the situation in Morocco. We will know whether it has worked in two or three weeks.