What’s going on with the dollar?

There was an interesting little shift in the dollar recently – one that was a little bit surprising at first look.

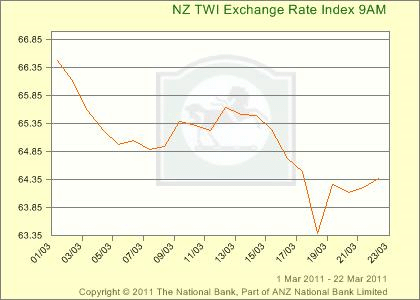

In the past month the dollar has been falling, first as a result of the Canterbury earthquake, then due to the 50bp cut in the official cash rate by the RBNZ. This all makes sense. But then the dollar dropped very sharply from around the 15th of March – this was well after the MPS, and nothing had happened in NZ. What was going on?

via NBNZ.

Specifically, the dollar dropped heavily against the Yen:

via NBNZ.

While the dollar was largely unchanged against the Aussie (apart from a random brief spike).

So what can we take from this? Well, what was going on on the 15th.

- A few days earlier a massive earthquake hit Japan.

- By the 14th and 15th there were increasingly dangerous explosions in Japanese nuclear power plants following the quake.

With nothing else going on, it appears that concerns around nuclear fallout in Japan was the primary driver of a steep fall in the New Zealand dollar – especially against the Yen.

Read this another way, Japan has been hit by a major crisis and its dollar is appreciating! I’ve seen this happen before in another large open economy called the United States – and I don’t like it.

So how does a negative shock to a country lead their dollar to appreciate – and why does it appreciate most strongly against countries like New Zealand and Australia. Well there are a few theories we can speculate with:

- Even with the crisis, Japan and the US are seen as “safe havens” while NZ and Aussie are “risky” – as a result, when people get nervous they sell risky assets (NZ currency) and buy safer assets (Japanese currency). My main issue with this is that we also saw the Yen appreciate against the US dollar – however it could just be that the Yen is an even safer asset than the US currency.

- A large amount of NZ’s external debt is financed by savings in Japan. If Japanese residents are going to pull money back following the crisis (or are at least expected to) this could drive down the value of the NZ dollar.

- The crisis in Japan is expected to interrupt, and reduce, global growth. Given that we are a small open economy we are more vulnerable to changes in the global economic cycle – leading to our dollar responding more aggressively to such events.

Update: Good comments regarding the issue from Eric Crampton and Miguel Sanchez.

There are a couple of things going on here:

1) Japan as a nation is a chronic saver, so that there is normally a continuous outflow of investment money, which works against the yen’s natural tendency to rise. When things get hairy, people are inclined to keep their money closer to home – the outflow tap is turned off, and that stabilising influence on the yen disappears.

Eric Crampton suggests repatriation flows from Japanese insurers. (My cruddy old computer stops me from replying on his blog.) I don’t think it’s insurers per se, as I gather they’re already loaded with yen-denominated assets. And as I’ve said, it may not be due to inflows, just the cessation of outflows.

2) The move was so violent because the Japanese are heavily into margin trading of currencies, and they are die-hard contrarians. So they would’ve been buying the NZ dollar on the way down, until they hit their loss limits on the 15th and had to sell up. For a more spectacular example of this, look at August 2007, when the accumulated NZ dollar positions were much larger than today.

Miguel, if that is your real name… Email me with the commenting problem. Maybe I can tweak settings.

I’d guess you follow currency moves a bit closer than I do. Buy your outflow cessation story.

I think the risk story is right. If the outflow story was correct we could expect the same to apply to all traded currencies. Let’s look at the Swedish Krona, the seventh most traded currency in the world (three or four places above the NZD:

/www.tititudorancea.com/z/jpy_to_sek_exchange_rates_japanese_yen_swedish_krona.htm

There was a blip in Yen-SEK from 13 to 18 March, but the cross rate is roughly back where it was. Similar story with the GBP (Sterling).

I’d agree with Miguel’s point number 3. $Yen has been trading heavily for a long time now, barely keeping its head above the important level of 80. After the earthquake the initial move was to sell Yen as the Nikkei collapsed. But within an hour or so the yen started to strengthen as the market focused on the yen repatriation story which has been around since I was trading the Yen in the 90s and long before that.

The resulting pressure forced the $ down and eventually the break of 79.75 was made. Once through there it fell very quickly to the low 76s. At the same time the NZ$ and OZ$ fell as cross trades went through. The break of 79.75 triggered massive amounts of option strikes which have been there for ages, not just in $Yen but in all the Yen crosses.

NZ/Yen fell 10% from 60.50 to 54.50……and now is at 61.35.

What does that tell us? Well it tells us that a lot of people lost money as option structures were knocked out; and that the market often overreacts to natural disasters. In this case the nuclear meltdown was a serious issue though at the same time it was unlikely the BOJ/MOF would have allowed a serious fall to continue.

In fact the NZ$ traded up to 75.70 on Friday, well above the 73.50 level pre-earthquake. Possibly earthquake related flows plus the usual short positioning and thin liquidity have exacerbated the move.

Which all goes to show that predicting currency moves is a mugs game.

“Which all goes to show that predicting currency moves is a mugs game.”

Yar – that is very true.

It is useful to try and understand things that will make a currency move, and what it is telling you about macroeconomic conditions – but I wouldn’t want to be in the game of predicting currency movements themselves …